The Location: Jefferson Street & I-40

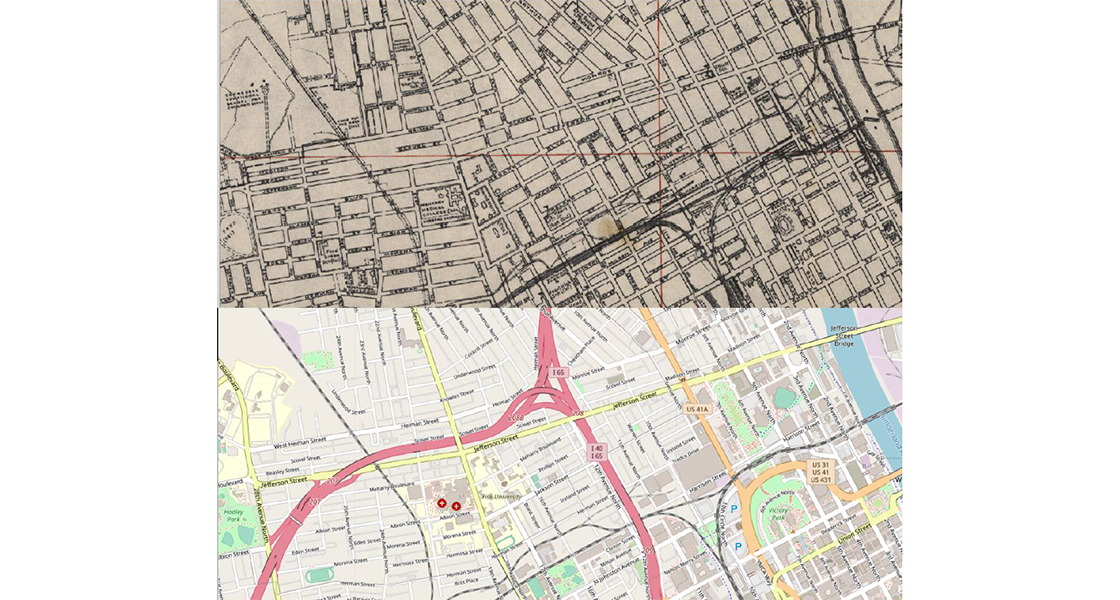

Fisk was established along Jefferson Street, described as “a wide footpath that evolved into a wagon road” from the local plantation to the Cumberland river in the antebellum years.[2] The school was rechartered in 1872 buoyed by the financial support of the Jubilee Singers’ tours and Jubilee Hall was completed as the school’s first permanent structure in 1876, with Jefferson Street directly behind it. Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State Normal School (later Tennessee State University or TSU) situated itself at the western edge of Jefferson Street in 1912. Meharry Medical College moved from South Nashville in the mid-1930s with Jefferson Street as its northern boundary. As Fisk, TSU, and Meharry emerged as anchors for Jefferson Street Mitchell describes the overall district as a “23-block area from Fifth Avenue, North, to Twenty-eighth Avenue, North” which came to answer the multiple calls of black life: religion, retail, and entertainment.

Jefferson Street’s heyday (considered by some to be 1935-1965) follows the arc of many Black commercial districts across the U.S. Jim Crow laws forced proximity and collaboration and the tumult and promise of integration and the Civil Rights movement began to pull away at the fabric. Underlying this was the effects of redlining in the 1930s by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation which labeled the entire area as “D” for hazardous.

Perhaps the biggest impact, however to Jefferson Street was the construction of Interstate-40 in the late 1960s. Despite resistance from a consortium of 40 community leaders self-named the “I-40 Steering Committee” which took their fight all the way to the Supreme Court, the Interstate continued as planned thereby decimating the district. According to Metro figures, 1,400 Nashvillians were displaced by the construction of I-40 and I-265 (which would become I-65). Houston writes that “the two-and-a-half-mile stretch of interstate would demolish a hundred square blocks” and lead to “the demolition of approximately 650 homes and 27 apartment buildings.” According to the Tennessee State Museum, the value of remaining housing dropped more than 30 percent. [3]