The black sea captains risked return to slavery by the Black Seamans Act of 1820 which required 40 days of quarantine for black crews and banning free blacks in ports or risk imprisonment. The blacks provided cheap, plentiful labor on the ships. The last deed of manumission dates to 1775 when Quaker Benjamin Coffin finally manumitted Rose and her sons Bristol and Benjamin Boston. There were no slaves on the island in 1775, yet Quakers opposed integration.

Anna Gardner, a Quaker experienced as a young child her mother and father hiding a runaway southern slave Arthur Cooper and his wife from southern slave hunters trying to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Anna Gardner became a vocal abolitionist and teacher at the Black School from 1836 to 1840[2]. She tried to advance her student, Eunice Ross to the public high school in 1838. Eunice Ross was denied entrance because of color despite having achieved the required score on the entrance exam. The prominent black community petitioned the town of Nantucket which denied her and then petitioned the Massachusetts Senate and House. Five years later, with the support of abolitionist in 1845. Massachusetts passed the first law in the United states guaranteeing equal education. Anti-slavery was a strong belief for Quakers, still integration was not accepted by most.

Quaker reasons for strong resistance to integration stemmed from beliefs of differences in color, odor, disease and concern for interracial mixing, In 1847 prejudice towards colored to integrate the school did not prevail. The school and church segregation issue continued long into Nantucket history. These beliefs continue to be deep seated in Nantucketer contemporary beliefs.

The African Baptist Church and School at 27 York street lot was sold to the black community by Jeffery Summons in 1825 for a token price of $ 10.50. [3] It is the oldest and only public building still in existence constructed and occupied by the island’s African Americans during the 19th century. This school was operated for 30 years in noncompliance with the Massachusetts law requiring integrated public schools. The school is in the area which was known as New Guinea at the Five Corners. This was in the area of town where African Americans lived and purchased property. The street names reflect the area such as Angola Street. Interesting to note is that in many cities with early settlement New Guinea was used to designate parts of towns for people of color. The colored cemetery is also located in the vicinity of New Guinea.

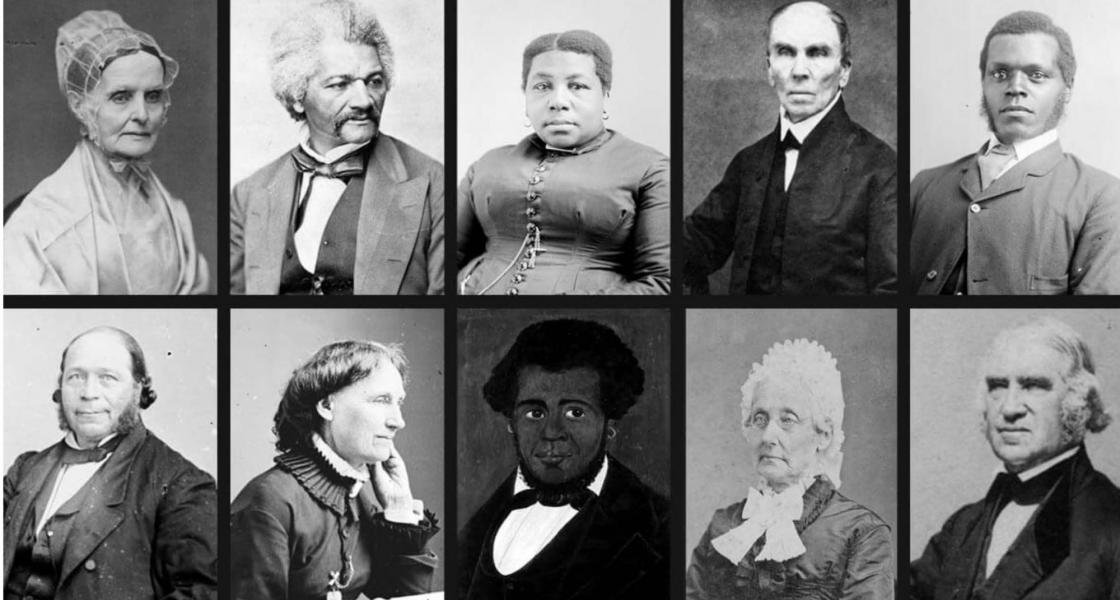

The Quakers support and belief in anti-slavery led them to be staunch abolitionists because that their evolving belief in the sinfulness of enslaving people. They organized anti-slavery conventions on the island with noted speakers such as Frederick Douglas. The second Anti-slavery convention of August 20, 1842 held at the Atheneum brought to light the extent of resentment to the abolitionist and their support of the abolitionists’ struggle to end slavery in the US slave states. Following a fiery speech by abolitionist, Stephen Foster who likened the religious leaders in enslaved states to the devil using money to buy slaves and continue slavery accusing them of being liars. This inhumane treatment of a race because of color was antithetical to Christian teaching. He accused them of complicity with clergy in slave states who tolerated the institution of slavery. He demanded that institutional churches separate themselves from their branches in slave states. The speech incited the local island inhabitants to storm and mob the Atheneum where the speech was given, throw rotten eggs and bricks and injuring the public. The Brotherhood of Thieves riot was named after the publication by Foster. It appears this riot was premeditated with possible knowledge of the selectmen and used as an excuse to distract from the major desegregation schooling issue at the time on island and positioned the abolitionist as against Christianity. It is interesting to note the comparison to the recent current day storming of the Capital. Perhaps an example of history repeating itself.