Before it was Shady Rest, the land was a colonial farm. The clubhouse, originally the farmhouse, was built in the mid eighteenth century by Ephraim Tucker. After that, the clubhouse became a tavern, and right before the turn of the twentieth century, the Westfield Golf Club bought the land, created a nine-hole golf course, and adapted the farmhouse to be the clubhouse. [1] The Westfield Golf Club did not allow black members, but the area surrounding the club was a largely black community. In 1921 the Westfield Golf Club merged with another golf club in the area and moved. They sold the club to the Progressive Realty Company, which was formed by a group of black investors including Henry Willis Sr. He and other investors gave the club a new life exclusively for the black community as the Shady Rest Country Club—the first black owned and the first African American country club in the United States. [2]

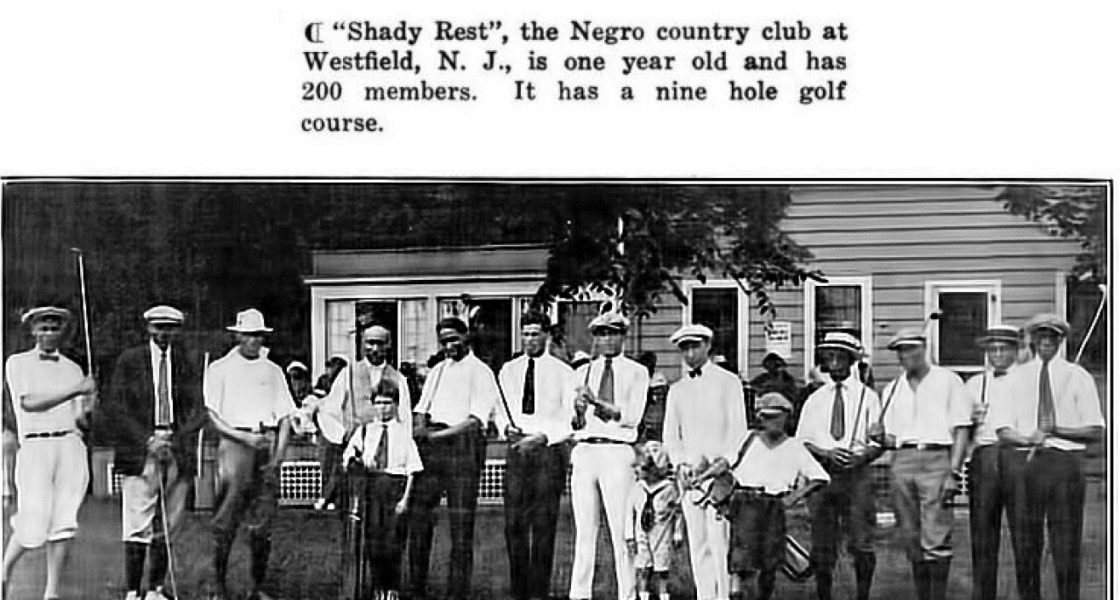

Shady Rest had a wide array of recreational activities for its members. Besides golf, members could partake in tennis, shooting and horseback riding. [3] However the real cultural magnitude of Shady Rest may have been in the nightlife and musical events. The clubhouse hosted dances and shows with prominent black artists such as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie and Duke Ellington, and activists such as W.E.B. Dubois who visited and lectured. [4] The club was even listed in the notorious Negro Motorist Green-Book. [5] With so much notable activity and music, some members recall white music enthusiasts loitering near the clubhouse just to listen to the music. [6] Shady Rest represented black success in America as a social institution that held great influence within the regional black community. [7]

One member of note, John M. Shippen Jr. was the first American-born golfer and the first African American to play in the U.S. Open golf tournament at Shinnecock Hills in 1896. After working at other local golf clubs, Shippen moved to Shady Rest in 1931 and was the club professional until he retired in 1968. [8] He cared for the course, played with club members, and taught some of the members’ children to play golf. [9]

Popularity grew for Shady Rest early in its forty-three-year lifespan. As a regional nexus of black culture, visitors travelled from nearby towns, cities like New York and other states such as the Carolinas. [10] The influence of Shady Rest spread in the time of segregation and discrimination. The black community had a private club just like the white clubs; they could socialize in a similar way. However, because of the limits to the proliferation of black culture, Shady Rest served a larger purpose as community institution with more influence in the black community than a white golf club may have had in the white community. [11]

In 1938 the club was struggling financially, and the township of Scotch Plains took ownership of the club. Eventually, Shady Rest Country Club became the Scotch Hills Golf Club, and the town opened it to the public. Public access also ended segregation—it was no longer a golf club just for the black community. Integration is often perceived as a positive trend from a moral and ethical standpoint. Jeffrey Sammons, a professor of history at New York University, questions the benefits of desegregating black institutions such as Shady Rest. In an interview, he comments on the cultural effects within the black community:

What kind of price have black people paid for integration? We tend to think about integration in positive terms…I don’t believe that African Americans have reached a true state of integration in this society; the integration tends to be superficial. Certainly, the kind of integration that we have has tended to hurt black institutions…So shady Rest’s demise has to be linked to larger issues beyond the municipality, beyond the community, but in terms of the effects of the kinds of integration that we see taking place in American society. [12]

As Sammons suggests, the price to pay for integration is the loss of a cultural institution for superficial social integration within which discrimination remains prevalent.

The legacy of Shady Rest as an impactful historic site is clear, though funding and recognition is limited. The club is listed on the New Jersey Register of Historic Places, and a preservation organization called Preserve Shady Rest is working towards nominating the site for the National Register of Historic Places based on its local, regional, and national significance. [13] Because of Shady Rest’s eventful history, and despite its current life as a public golf course, it remains a historically notable place of black recreation, culture, and community influence.

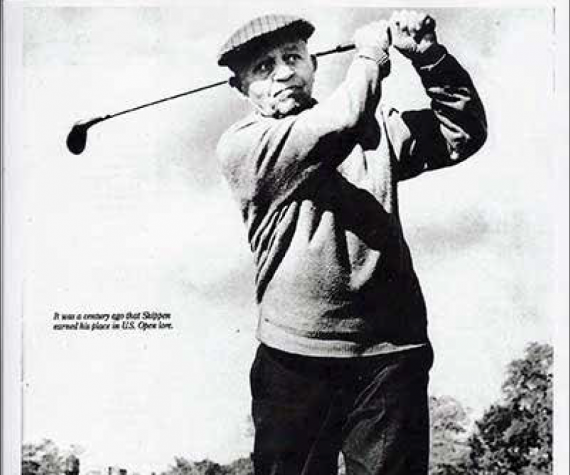

Images courtesy of http://www.preserveshadyrest.org/

Endnotes

1. Preserve the Shady Rest Golf & Country Club, Preserve the Shady Rest Committee, accessed 08 February 2021, http://preserveshadyrest.org/index.html.

2. Preserve the Shady Rest Golf & Country Club.

3. Preserve the Shady Rest Golf & Country Club.

4. Barry Carter, “It Was the Center of African-American Society in N.J. Locals Say We Need to Preserve it.” NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, 16 February 2020, accessed 08 February 2021, https://www.nj.com/news/2020/02/it-was-the-center-of-african-american-society-in-nj-locals-say-we-need-to-preserve-it.html.

5. Preserve the Shady Rest Golf & Country Club.

6. Cathleen M. Londino, A Place for Us, directed/produced by Lawrence Londino (Montclair, NJ: Montclair State University DuMont Television Center, 2013), web: YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qgM3Moe2mk4.

7. A Place for Us.

8. Carter.

9. A Place for Us.

10. Carter.

11. A Place for Us.

12. A Place for Us.

13. Preserve the Shady Rest Golf & Country Club.

References

Carter, Barry. “It Was the Center of African-American Society in N.J. Locals Say We Need to Preserve it.” NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. 16 February 2020. Accessed 08 February 2021. https://www.nj.com/news/2020/02/it-was-the-center-of-african-american-society-in-nj-locals-say-we-need-to-preserve-it.html.

Londino, Cathleen M. A Place for Us. Directed/Produced by Lawrence Londino. Montclair, NJ: Montclair State University DuMont Television Center), 02 September 2013. Web: YouTube. Accessed 08 February 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qgM3Moe2mk4.14

Preserve the Shady Rest Golf & Country Club. Preserve the Shady Rest Committee. Accessed 08 February 2021. http://preserveshadyrest.org/index.html.