The Foster Site: A Story of Strength in the Shadows

More than a symbol of freedom, the Foster Site is a story of strength and the ability of an entire community to defy racist institutions and become landowners. In many respects, Kitty Foster attained the unattainable, owning and managing a home at a time when government institutions and the private housing market continuously worked to suppress equal opportunities for African-Americans and even more so, African-American women. Its location on what are now the UVa grounds is further symbolic of a university that has continuously encroached its borders into poor and working-class communities of color, like that of Canada. Thus, the Foster Site’s preservation is critical to not only telling the story of Kitty Foster and her neighbors, but to empower the next generation of trailblazers in the movement for racial justice and equality.

Questions of Intention and Tokenism in Charlottesville’s Black Community

The Foster site today has largely fallen out of public discussion, but the pathway to the site’s dedication in 2011, its addition to the Virginia Landmarks Register, and inclusion in the NRHP in 2016 was a tumultuous twenty-year process. It raised questions less on how to best represent Foster’s memory, but instead on the viability of an all-white team of archeologists, anthropologists, and preservationists to adequately lead the process. A 1994 Washington Post article reported concerns from Black archeologists and anthropologists in the field that the Foster Site study was a ‘superficial offering’ to the Charlottesville Black community as University officials sought to expand into Black neighborhoods.

These initial concerns have seemingly been assuaged since the 1990s when the University began a 15-year archaeological study led in part by the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at UVa, as well as a local neighborhood task force. The University also contracted Walter Hood, a preeminent landscape architect and author of Black Landscapes Matter, to construct the final vision for the site. Whether the University’s intentions were devoid of ulterior motives is ultimately unclear, but since the site’s completion, the area around the Foster Site has been razed and redeveloped to accommodate more than 300,000 square feet of new university buildings. Although the presence of a heritage site should not inherently stagnate progress in terms of meeting community needs, further questions should be asked regarding the site’s ability to authentically convey the Canada neighborhood’s culture, to steward community relations today, and to inform social justice issues going into the future.

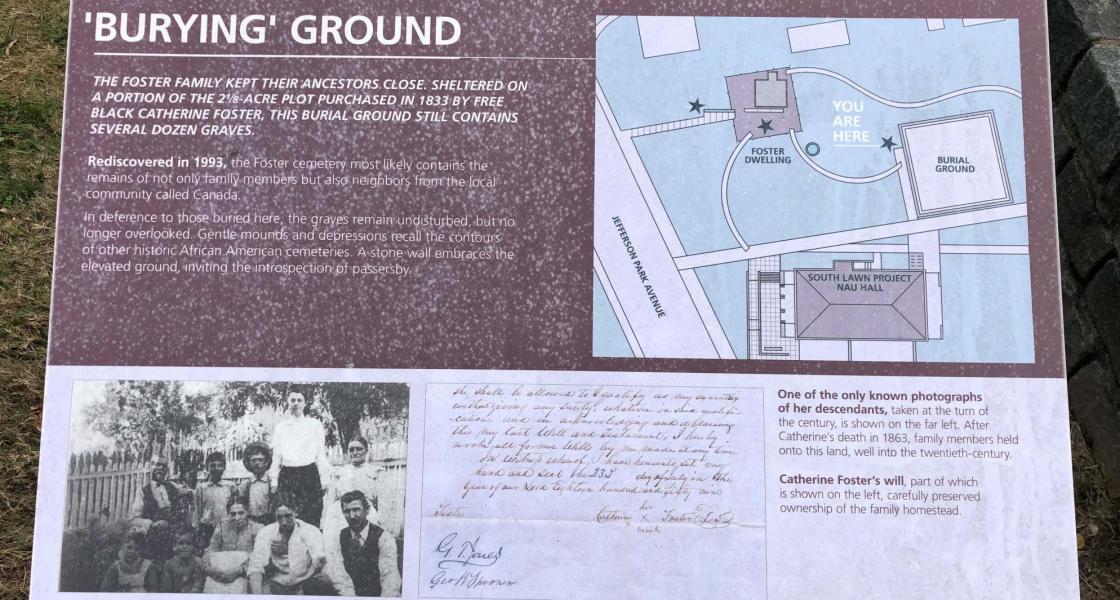

A Community Forgotten and Unrecognized

Although not a point of public discourse, there is no information on the Foster Site or elsewhere in the vicinity that signifies the importance of the Canada community in Charlottesville’s history. The single informational sign (Figure 3) on the site provides no description of the community or its culture, the significance of Black homeownership during the period, or the University’s role in the neighborhood’s demise. The Foster Site also lacks any public information regarding ongoing programming or facilitation of discussions related to Kitty Foster and her community. As this site is located on UVa grounds, UVa is responsible for leading discussions that not only involve the site’s history, but also its significance in the context of the ongoing discussions of racial justice in Charlottesville and beyond. The failure to incorporate Canada’s significance in the context of the U.S. South and Charlottesville in the Foster Site, as well as the lack of public programming to provoke discussion on social justice movements today is a missed opportunity for UVa to elevate Black history that is so often left out of its own institutional story.

Looking Ahead: Lessons Learned for Institution-led Heritage Sites

UVa’s Kitty Foster Homestead and Cemetery provides important lessons to the development of future civil rights heritage sites, and more specifically, to institutionally led projects. Plans must not be perfunctory, but instead participatory and a reflection of the narratives that are to be told on the site. Heritage sites like the Foster Site must also seek to memorialize while simultaneously interrogate history and forge pathways to address injustices present in communities today. Civil rights sites are not to be tokenistic gestures, but instead opportunities to acknowledge, reckon, and celebrate a rich history brought to life in physical space.