While the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act cannot be overlooked in having enabled equitable treatment in workplaces and having required the built environment to guarantee universal accessibility, it still seems that public perception has yet to change. So why the disconnect between the existing political initiatives and our actual attitudes towards the disability community? How do we address this disparity?

One explanation is that disability communities have often been and still are being made invisible, that is, excluded from many parts of our society including from popular culture, academics, and even in TV advertising. [3] The lack of representation of people with disabilities also extends to our public memoryscapes; there is a dearth, if not a total absence, of historical markers, public monuments or memorials dedicated to memorializing people with disabilities let alone the disability rights movement that challenged the way disabilities are perceived in the US.

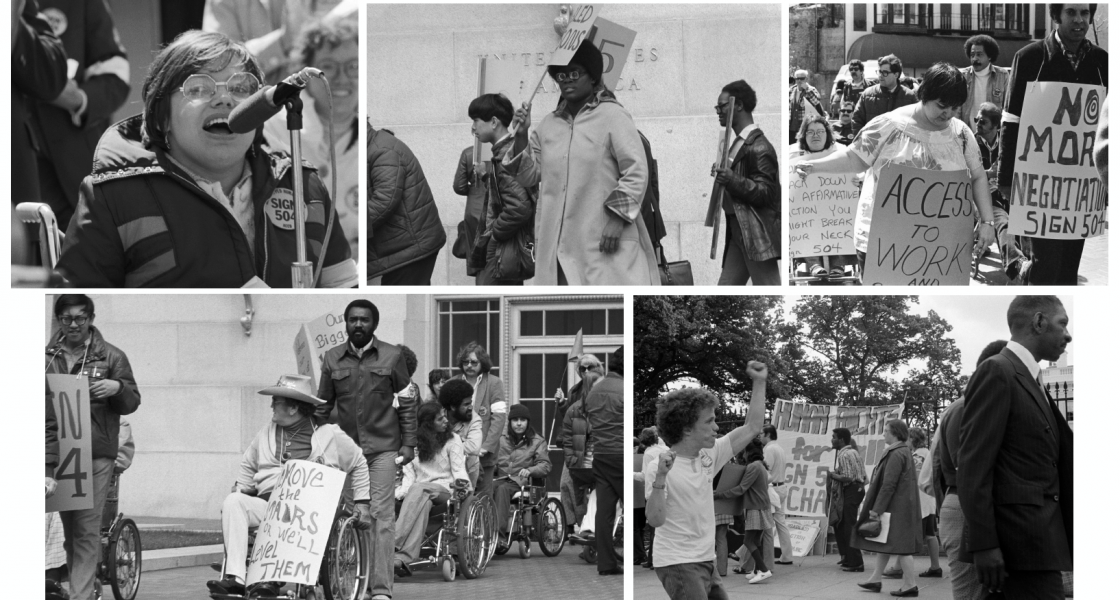

The landmark status given to the ADA often overshadows the significance of the events that preceded it, notably the 504 Sit-In Protests of 1977 in San Francisco. On April 5th of that year, activists and demonstrators across the nation began occupying regional offices of the federal Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) responding to the delayed execution of the Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act meant to prevent employment discrimination based on disability. [4,5] While most of the protests ended within a couple of hours or days, protestors in San Francisco took over the HEW office and began what would be known as the 504 Sit-In lasting 26 days. On April 28th, the regulations were finally implemented.

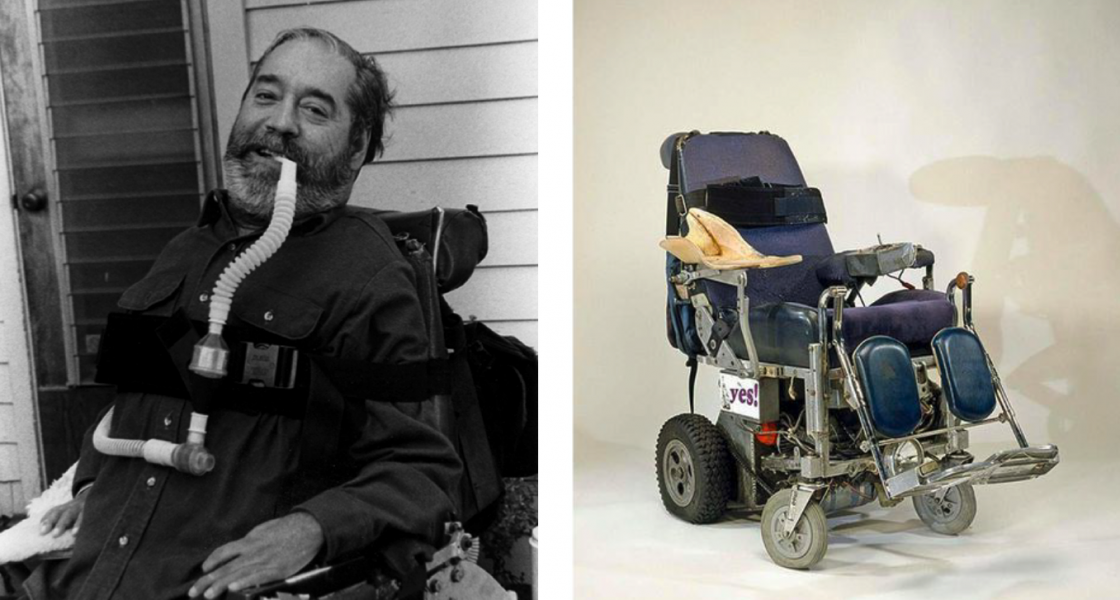

The fact that the 1977 takeover remains the longest non-violent occupation of a U.S. federal building in history isn’t the only aspect that makes this event historic. The 504 Sit-In is an incredible story of intersectionality and empowerment. Men and women with different levels of physical capabilities as well as other organizations such as the Black Panther Party, Gray Panthers gave their sweat and hearts to the sit-in. [6] It is also known that women wheelchair riders led the San Francisco protest. [7] Given all this, it only seems natural to think that there would be some physical reminder celebrating the event but sadly there have not been any made so far; the closest to its public memorial being a mural of black and white photographs of the 504 Sit-In protest at Ed Roberts Campus ramp at UC Berkeley.8 Much of the artifacts and oral histories related to the protest remain as traveling exhibits, in select museums and scattered throughout online mediums.

What we see instead in the current public memoryscape on America’s disability history is the FDR Memorial and the Helen Keller statue in Washington D.C., the dominant narrative seeming to be that of personal overcoming. While some may argue something is better than nothing, they send messages that miss the essence of what the 504 Sit-In protest was about: “to reject charity and pity but demanding equality.” [9] In other words, Section 504 and subsequently the ADA were pivotal achievements in having placed the burden on the society, rather than on the disability community, to overcome and rethink the socially constructed notion of disability as a barrier that distinguishes the able from the disabled.

As the saying goes - “out of sight, out of mind” - the absence of overt efforts to memorialize disability rights movement in our built environment can potentially be interpreted as a social cue to continue to consider disability as an issue of charity, rehabilitation and pity pushing the disability community further into invisibility. [10] Without proper and adequate preservation and memorialization of the disability rights movement at a national scale, we will continue forget how America was able to get to the ADA in the first place; it was not the political acumen of few elite figures but the persevering efforts of the American disability community along with other minority groups that challenged national thinking on disability. As Kitty Cone, a participant in the 504 Sit-In rightfully stated, “In the face of government ignorance, we persisted and won. No one gave us anything. [11]

Endnotes

1. Anne V Golden, “An Analysis of the Dissimilar Coverage of the 2002 Olympics and Paralympics: Frenzied Pack Journalism versus the Empty Press Room,” Disability Studies Quarterly 23 (2003), https:// doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v23i3/4 .

2. Nexis Uni, s.v. “Olympics” and “Paralympics,” last modified February 6th, 2021.

3. Golden, “An Analysis of the Dissimilar Coverage.”

4. Julia Carmel, “Before the A.D.A., There Was Section 504,” The New York Times, July 22, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/22/us/504-sit-in-disability-rights.html.

5. Britta Shoot, “The 1977 Disability Rights Protest That Broke Records and Changed Laws,” Atlas 5 Obscura (Atlas Obscura, November 9, 2017), https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/504-sit-in-san-francisco- 1977-disability-rights-advocacy. Protests occurred in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Dallas Denver, Philadelphia, New York, Seattle and HEW HQ in Washington D.C.

6. Ibid.

7. “The Untold Stories Of The 504 Protests,” Patient No More (San Francisco State University Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability), accessed February 8, 2021, https://longmoreinstitute.sfsu.edu/patient-nomore/untold-stories-504-protests.

8. “Mural,” Patient No More. https://longmoreinstitute.sfsu.edu/patient-no-more/mural. The Ed Roberts Campus is a nonprofit (501c3) corporation formed by disability organizations rooted in the Independent Living Movement of People with Disabilities founded by Ed Roberts.

9. Andrew Grim, “Sitting-in for Disability Rights: The Section 504 Protests of the 1970s,” National 9 Museum of American History (Smithsonian Institution, July 8, 2015), https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/ sitting-disability-rights-section-504-protests-1970s.

10. Ibid.

11. Patient No More, https://longmoreinstitute.sfsu.edu/patient-no-more/ 11

Resources

Carmel, Julia. “Before the A.D.A., There Was Section 504.” The New York Times, July 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/22/us/504-sit-in-disability-rights.html.

Golden, Anne V. “An Analysis of the Dissimilar Coverage of the 2002 Olympics and Paralympics: Frenzied Pack Journalism versus the Empty Press Room.” Disability Studies Quarterly 23 (2003). https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v23i3/4.

Grim, Andrew. “Sitting-in for Disability Rights: The Section 504 Protests of the 1970s.” National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution, July 8, 2015. https:// americanhistory.si.edu/blog/sitting-disability-rights-section-504-protests-1970s.

Nexis Uni, s.v. “Olympics” and “Paralympics,” last modified February 6th, 2021.

Shoot, Britta. “The 1977 Disability Rights Protest That Broke Records and Changed Laws.” Atlas Obscura. Atlas Obscura, November 9, 2017. https://www.atlasobscura.com/ articles/504-sit-in-san-francisco-1977-disability-rights-advocacy.

Patient No More. San Francisco State University Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://longmoreinstitute.sfsu.edu/patient-no-more/untold-stories- 504-protests.

![[Image description: Two people under a blanket sleeping at the foot of a staircase near an empty wheelchair.] Some of the demonstrators remained inside for almost a month, making it among the longest occupations of a federal building in U.S. history. (Image courtesy of HolLynn D'Lil via New York Times) people sleeping on chairs](/sites/default/files/styles/text_image_slider/public/2021-03/roha_5625566_942v11649_Ro_casestudy_slides.jpg?itok=ZsVd-ysO)